Cobb Duels Sisler for King of The Hill

November 2, 2025 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

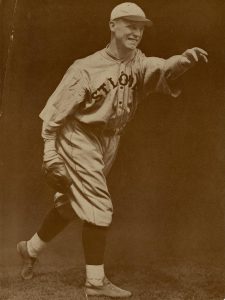

Given George Sisler’s 15-year career and lifetime .340 batting average, it is a bit surprising that he had but two American League batting championships – and he had to hit more than .400 (.407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922) to obtain them. The competition was stiff in those days, and one of Sisler’s regular competitors was Ty Cobb. Their careers overlapped from 1915 through 1928. But the competition wasn’t limited to what they did in the batting box.

Given George Sisler’s 15-year career and lifetime .340 batting average, it is a bit surprising that he had but two American League batting championships – and he had to hit more than .400 (.407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922) to obtain them. The competition was stiff in those days, and one of Sisler’s regular competitors was Ty Cobb. Their careers overlapped from 1915 through 1928. But the competition wasn’t limited to what they did in the batting box.

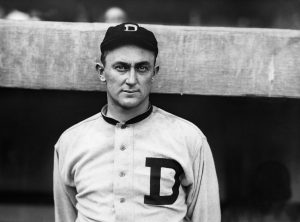

In 1918 Cobb won the AL batting title with a .384 average. Sisler was in third place at .341, just a tad above his career average of .340. (If you’re wondering, George Burns of the A’s was second at .352.) The 1918 season deserves an asterisk, as the season had been shortened due to World War I. The season ended on Labor Day, by which time Cobb had clinched the batting title.

In 1918 the Red Sox won the pennant by 2.5 games over the Indians. For the other American League teams, Labor Day weekend was merely a matter of playing out the schedule. The Tigers would finish in seventh place, 20 games out. Thanks to making up rainouts, they had to end the season with back-to-back double-headers against the Browns and the White Sox.

On the second game of the Sunday, September 1st double-header against the Browns, the remaining fans of the estimated 8,000 fans at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis got to witness a rarity. With the Browns ahead 5-2 at the 7th inning stretch, starting pitcher George Cunningham trotted out to center field. This was not without precedent, as Cunningham appeared in the outfield 20 times in 1918. What was unprecedented was his replacement. Center fielder Ty Cobb swapped places with Cunningham and took the mound. What was manager Hughie Jennings thinking? Well, he still had a double-header to play the next day, so perhaps he was just trying to save wear and tear on the pitching staff.

Cobb had been known to pitch batting practice now and then, but he had never appeared as a pitcher in 14 seasons with the Tigers. Fans thinking of leaving early might have changed their minds. After all, Ty Cobb on the mound was something no one had ever seen before.

Cobb had been known to pitch batting practice now and then, but he had never appeared as a pitcher in 14 seasons with the Tigers. Fans thinking of leaving early might have changed their minds. After all, Ty Cobb on the mound was something no one had ever seen before.

The results were not that bad. Cobb pitched two innings, giving up three hits and one earned run.

After 8 innings with the hometown team ahead 6-2, Brownie nation was in for yet another treat. In the top of the 9th inning, first baseman George Sisler came in to nail down the victory for the Browns. He gave up one hit and no runs. So the fans still on hand at Sportsman’s Park by the end of the second game could tell their grandkids that they saw Ty Cobb and George Sisler on the mound in the same game. This was not Sisler’s first appearance on the mound in 1918, as he had pitched 7 innings in a losing (but no-decision) effort against the Yankees just four days before.

In 1918 some of the Browns fans were surely aware that Sisler had started out as a pitcher. In his rookie year of 1915 he was mostly a position player but he had logged 70 innings on the mound. In 1916 he hurled 27 innings. In 1917 he was strictly a position player. So his 1918 appearances on the mound might have been a bit of a surprise, but they were not unprecedented. Sisler hurled no more that season, but Cobb was not finished.

The next day the Tigers would close out the season with a double-header at Navin Field (aka Briggs Stadium and Tiger Stadium) in Detroit. If it had been a disappointing season in Detroit, the same was surely true for their opponents, the White Sox. After winning the World Series in 1917, they were well below .500. At day’s end they would finish the season with a 57-67 record, good for 6th place.

Retrosheet includes a curious editorial comment on the second game. At the beginning of the play-by-play log, it says “Farcical final game of season.” Now what does that mean? My guess would be that with nothing to play for and anxious to get the season over, the pitchers were throwing only fastballs and batters were swinging at anything they could reach. A short game time would verify that, but the box score does not include that statistic.

Or it could refer to the Tigers starting pitcher, 41-year-old “Wild Bill” Donovan, who had been a mainstay of the Tiger pitching staff, winning 140 games from 1903 through 1912, including the Tigers’ pennant years from 1907 through 1909. Managing the Yankees from 1915 through 1917, Donovan pitched in 9 games in 1915, 1 in 1916 and none in 1917. In 1918 he returned to the Tigers as a coach. He pitched in one game, hurling one inning in relief against the White Sox in a July 4th contest at Comiskey Park.

Donovan’s opposite number was Ed Cicotte, who went the distance, giving up 21 hits but only 7 runs. At day’s end his record was 12-19, but he finished the 1918 season with his integrity intact, which would not be the case in 1919.

After five innings, Donovan was doing surprisingly well. He had given up just one earned run and the Tigers led by 4. Since he was long past his prime, it was not surprising that he came out of the game, but his replacement was probably a surprise. Tiger fans had likely read about Cobb’s pitching performance in the morning papers. If they wished they could have seen him in action, now they had their chance.

It was almost a carbon copy of his previous appearance. Two innings pitched, one earned run. Cobb’s back-to-back appearances were highly improbable, but so was the appearance of the next pitcher, Bobby Veach, the Tiger left fielder, who had been with the team since 1912 and had never pitched in a game before. The results were similar to Cobb’s: two innings pitched, just one earned run. In the player shuffling that went on after the 7th inning, Cobb was moved to third base for the first and last time in his long major league career.

Now let us flash forward seven years. Unlike the 1918 season, the 1925 season was comprised of the usual 154-game schedule, but once again, most teams were just playing out the schedule by the final weekend of the season. That was the case on October 4, 2025, when the Tigers closed out the season with a double-header against the Browns in St. Louis.

On paper, the two teams were evenly matched. The Browns (82-69) had clinched third place. There was no way they could overtake the second-place A’s, who had already finished the season at 88-64. On the other hand the Tigers (79-73) were in a battle with the White Sox (78-75) for fourth place. No big deal, but by finishing fourth they could stay they were in the first division, which used to mean something in an eight-team league before divisional play came along.

But there was more at stake. In those days the first division teams shared in the proceeds of the World Series. They second, third, and fourth-place teams might have been also rans, but they were competing for 7.5%, 5% and 2.5% of the take, respectively. Given major league salaries at the time, it was not a bad year-end bonus – particularly for fringe players.

After a 10-4 victory in the first game of the October 4th double-header, however, the Tigers were 80-73 and had clinched fourth place. So there was nothing left to play for in the second game.

I don’t know how many of the estimated 12,000 fans were still around by the end of the second game, but those who stuck it out saw a unique moment in baseball history. Detroit starter Lil Stoner and Browns starter Ed Stauffer had been swapped out for a couple of rookies, Ownie Carroll for the Tigers, Chet Falk (brother of Bibb Falk) for the Browns. In the top of the 7th inning, the Tigers had a lead of 11-5. It’s possible a number of fans were getting up to leave and head home for Sunday dinner. If so, a lot of them probably changed their mind when they saw who was coming in to pitch for the Browns. George Sisler pitched the seventh and eighth innings, yielding just one hit, one walk and no runs. But that was not the only surprise of the day. In the bottom of the 8th inning, Ty Cobb took the mound for the Tigers.

Of course, today we marvel at the fact that two Hall of Famers – position players, mind you – were competing against one another as pitchers. Of course, the Hall of Fame didn’t exist in 1925, so the fans in attendance at the game couldn’t conceive of that.

But there was more. In 1925 both Sisler and Cobb were player-managers. One wonders if Cobb would have taken the mound if Sisler had not done so. Cobb hit into a double-play to end the top of the 8th, so perhaps he was hoping to face Sisler. The Browns went three-up, three-down in the bottom of the 8th and Sisler was due up in the 9th. Unfortunately, the game was curtailed on account of darkness, so we’ll never know how that Cobb versus Sisler confrontation would have played out.

So the fans in Sportsman’s Park who stuck it out had seen a game unique in baseball history. Two player-managers, both former batting champions, both of whom had hit .400 twice, had inserted themselves into the game as pitchers. How many fans were aware that the two men had also appeared as pitchers in the same game in 1918?

The lesson for baseball fans is clear. Don’t turn your nose up at “meaningless” games. On any given day you might witness baseball history.

It was true 100 years ago and it’s true today.