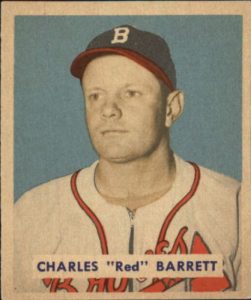

Red Barrett, Efficiency Expert

January 21, 2026 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

The starter was holding his own. Pitching into the 5th inning, he had yielded just one unearned run. Suddenly the manager came out of the dugout and beckoned for a new pitcher, a puzzling move to be sure. As it turned out, the pitcher who came out of the bullpen was ineffective, as were his successors. They yielded 14 more runs and the game. I later learned that the starting pitcher was on a strict pitch count limit of 70. Given that regimen, his chance of going five innings and earning a victory were slim. And a complete game? He didn’t have a snowball’s chance…unless hell froze over. And that’s one possible explanation to account for what Charles “Red” Barrett accomplished on August 10, 1944.

The starter was holding his own. Pitching into the 5th inning, he had yielded just one unearned run. Suddenly the manager came out of the dugout and beckoned for a new pitcher, a puzzling move to be sure. As it turned out, the pitcher who came out of the bullpen was ineffective, as were his successors. They yielded 14 more runs and the game. I later learned that the starting pitcher was on a strict pitch count limit of 70. Given that regimen, his chance of going five innings and earning a victory were slim. And a complete game? He didn’t have a snowball’s chance…unless hell froze over. And that’s one possible explanation to account for what Charles “Red” Barrett accomplished on August 10, 1944.

Red Barrett’s career trajectory was a peculiar one. Signed by the Cubs in 1935, he started his career with Ponca City of the Class C Western Association. He was 20-24 in two seasons with inflated ERAs (4.66 in 1935 and 5.38 in 1936). The Cubs let him go, but he persuaded another Western Association team, the Muskogee Reds, to sign him, boasting that he would lead them to a pennant. According to his teammates and other observers, Barrett was not lacking in confidence. Since he was a classic ginger (fair-skinned, freckled, and redheaded) and Irish, I’m tempted to say he was given to blarney. Since he was a professional singer in the off-season, I’m also tempted to say he was an Irish tenor, but I can’t find any information on his vocal range.

Given the mediocrity of his first two seasons of professional ball, it was incredibly bold to predict he could post a winning record, much less lead a team to a pennant. Well, as Dizzy Dean once pointed out, it ain’t bragging if you can do it. Barrett was no Dizzy Dean, but he logged a 24-12 record in 1937, and Muskogee finished first (but lost in the playoffs – no promises made about the post-season). That was good enough to persuade the big-league Reds to bring him up for a cup of coffee at the end of the season. Thereafter, he was on the shuttle between the Reds and their top minor league affiliates (the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League in 1938; the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association in 1939 and 1940).

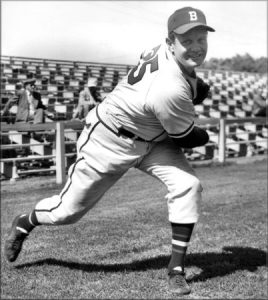

After a disappointing 1940 season (5-13, 4.74), he was demoted to the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association. He responded with 20 victories. Promoted back to Indianapolis in 1942, he responded with another 20-victory season. Could he do that for a major league team? Barrett was 28 at the outset of the 1943 season and probably wondering if he was fated to be a career minor leaguer.

He need not have worried. The military draft had wreaked havoc on major league pitching staffs, thus creating an opportunity for the likes of Barrett and increasing his chances of returning to the big leagues, albeit not with the Cincinnati Reds.

The Boston Braves were not one of the more storied National League franchises in those days, to put it kindly. In 1942 they had a 59-89 record, good for a 7th place finish under the tutelage of Casey Stengel. Johnny Sain and Warren Spahn got their first big league experience that year but “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” would not be coined till after the war. The Braves had two decent starters, Jim Tobin (who lost 21 games but led the league in complete games with 28 and IP with 287.2) and Al Javery who led the league with 37 games started. And after those two guys? Well, the slogan in 1942 could have been “Tobin and Javery and the rest are unsavory.” Hence an opportunity for Red Barrett after the Braves purchased him from the Reds.

In 1943 the Braves were marginally better with a record of 68-85, good for sixth place. Even so they had a better season than manager Casey Stengel, who broke a hip in an auto accident in mid-season and was succeeded by Bob Coleman. Barrett was 12-18 with a 3.18 ERA in 255 IP. Nothing to write home about but good enough to assure Barrett of another spot in the rotation in 1944.

1944 was not a good season (9-16, 4.06 in 30 starts) for Barrett but the same was true of the Braves, who fashioned a 65-89 record and another sixth-place finish. They had no one better to insert into the rotation, so manager Coleman continued to write Barrett’s name in as a starting pitcher, and in one of those starts Barrett wrote his name into baseball history.

On the night of August 10th the Braves, with a record of 42-60, were in Cincinnati. At 55-44, the Reds were at least within shouting distance of a pennant race (they would finish third with a respectable 89-65 record but 16 games behind the Cardinals, who would log 105 wins). The Reds had made history on June 10 when 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall, the youngest pitcher to ever play for a major league team, took the mound. On August 10th they would be involved in another record-setting game.

When Barrett took the mound that night, he was a mere 6-11. His opposite number was Reds ace Bucky Walters, who was 16-5 on his way to a 23-win season and a 198-win career. Advantage Cincinnati, right? Maybe not. Barrett had defeated Walters three times in 1943.

Barrett gave up a single to center fielder Gee Walker in the first inning, another single to shortstop Eddie Miller in the 6th, and that was it. No surprise that he ended up with a complete game shutout. The surprise was that he managed to do it with 58 pitches. No one has ever thrown a complete game with fewer. Obviously, Barrett was pitching to contact (he recorded no strikeouts) and the Reds were swinging early. He walked no batters so we can assume he was around the plate.

Those 58 pitches break down to an average of 6.44 pitches per inning. He faced just 29 batters, so that’s an average of two pitches per batter. I guess we can also conclude that aside from four foul pop-outs, the Reds hit very few foul balls.

Bucky Walters wasn’t exactly taxing his arm either. He gave up just six hits and one earned run. He walked one and struck out one while going the distance. His efficiency, combined with Barrett’s, resulted in a game that lasted just one hour and fifteen minutes. It was the shortest night game ever played, which might not have been a big deal in 1944, given the short history of night games. But eight decades later, it remains the shortest night game ever played.

Barrett and Walters were not trying to set any speed records. It just worked out that way. Could there be a reason why the hitters were so reluctant to take pitches? One occasionally hears stories of teams picking up the pace because they had to catch a train, but the Braves weren’t going anywhere. The August 10th contest was the second of a four-game series.

Of course, one occasionally sees games sped up under threat of rain with the team in the lead trying to get past the 5-inning mark to make it an official game in case the skies open. But there was no rain that day in Cincinnati. The city was in the midst of a heat wave with an 8-day streak of days in the upper 90s. Those conditions are more likely to result in slowdown rather than a speed-up.

The average game time in 1944 was 2:01. Obviously, game times of less than two hours were common. Given the right circumstances, a game time of 1:15 was highly unlikely but conceivable…not unlike hell freezing over. Given Barrett’s philosophy of pitching, however, it was more likely. In an interview he gave six years earlier, he asserted, “I’m no strike-outer. These strikeout pitchers are chumps in my book. Me, I try to make them hit that first ball….I’d rather get that batter out on one pitch and save my arm. I am a control and if you don’t mind my saying it, smart pitcher.”

Whether lacking in control, smarts, or both in the remainder of his 1944 appearances, Barrett finished the season with a 9-16 record and a 4.06 ERA. His two seasons with the Braves had proved he could be a mediocre pitcher at the big league level, albeit at a time when the talent level was at a low ebb. Surprisingly, at age 30 in 1945, he kicked it into high gear. After nine games and two victories with the Braves, he was traded to the Cardinals, for whom he won 21 games with a 2.74 ERA. He led the league in CG (24), wins (23), and IP (284.2). He somehow managed to achieve all this while also leading the league in hits yielded (287). On September 2nd, his 20th victory, a 4-0 win over the Cubs, was a memorable one, as he threw a one-hitter, pitching to the minimum of 27 batters after the Cubs’ sole base runner, Lenny Merullo, was thrown out stealing.

In 1945 Barrett was an All-Star for the only time in his career but he did not play. Actually, nobody did since the game was canceled due to wartime travel restrictions. A tribute of sorts was his appearance on the cover of Life magazine during spring training in 1946. After that it was all downhill. World War II was history, so the Cards’ pitching staff was beefed up with returning veterans and the other NL teams welcomed back proficient hitters whose careers had been interrupted.

In 1946 Barrett finished with a 3-2 record and a 4.03 ERA in a mere 67 IP for the Cardinals. His first victory of the season on June 8th was notable, however. Again, he was just one batter removed from a perfect game, surrendering only an eighth inning single to Del Ennis in a 7-0 victory over the Phillies. A consolation prize for his disappointing season was a World Series championship, but he did not pitch in any of the seven games against the Boston Red Sox.

After the 1946 season the Cards sold him back to the Braves, but the results were still ho-hum: collectively, 19-21 over the next three seasons. He did have a couple of scoreless appearances in relief in the 1948 World Series against the Indians, but after he logged a 5.68 ERA in the 1949 regular season, he became expendable. So, his 11-year MLB career came to an end. Despite the undeniable highlights in his career, the overall record was that of a journeyman: 69-69 and a 3.53 ERA.

After the 1946 season the Cards sold him back to the Braves, but the results were still ho-hum: collectively, 19-21 over the next three seasons. He did have a couple of scoreless appearances in relief in the 1948 World Series against the Indians, but after he logged a 5.68 ERA in the 1949 regular season, he became expendable. So, his 11-year MLB career came to an end. Despite the undeniable highlights in his career, the overall record was that of a journeyman: 69-69 and a 3.53 ERA.

Barrett’s playing career, however, was not over. In 1950 he was back where he started: In the Cubs’ minor league system. He closed out his playing career at age 38 playing for the Paris Indians of the Class B Big State League.

After Barrett died in 1990, the Hot Stove League in Wilson, North Carolina, where he had retired, printed a tribute to him that noted “He played the quickest round of golf of anyone in the Unites States of America.”

Makes sense to me. In baseball and golf, the participants don’t get paid by the hour. All too often, however, it seems that way to the spectators.